Exploring the possibilities for innovation in the field of medicine and beyond.

Friday, December 23, 2011

Patients as Consumers: The Milkshake Mistake

I keep running up against the tension over characterizing patients as consumers. Although Nobelist Paul Krugman explicitly said "Patients are not Consumers" in a NYTimes column this past April, other business and economics notables, such as Clayton Christensen, encourage innovation in the world of medical care delivery modeled on consumer service industries.

Personally, when musing casually about patients as consumers, I've found myself alternately rebuffed (for blaspheming the sacred doctor-patient relationship) and encouraged (for probing methods of caring for patients' true needs) by my medical seniors. I've since learned to test the sensitivities of my audience before even hinting at comparing patients and consumers.

Here, rather than attempt to put the issue to rest, I simply want to present one example where viewing patients as consumers stands not only to improve their care, but to actually deepen the humanist goals of those who are otherwise afraid of commoditizing a covenant.

The Milkshake Mistake

Clayton Christensen and others have used a case study of McDonalds to illustrate the value of stepping inside the consumer's shoes. Specifically, how do you see the value of your service, not as what you think the consumer should desire, but as what they truly seek.

The example, adopted from an article in the Harvard Business Review, has been termed the Milkshake Mistake. Briefly, McDonalds was conducting product research on how to sell more milkshakes. Researcher Gerald Berstell was surprised to discover that most shakes were purchased by early morning commuters who used the shakes as a one-handed tasty breakfast that was easy to eat and kept them awake in the car. After Berstell had examined the milkshake from the consumers' perspective, McDonalds could abandon their assumptions about what consumers wanted from their milkshakes, and instead tailor milkshake delivery more precisely to their consumers true needs.

As Christensen details in The Innovator's Prescription, this speaks powerfully to health care. Providers, with their years of training and advanced expertise, may have assumptions about the desires of their patients that are not consistent with what patients truly seek from their doctors. Although this kind of market research draws directly from the business world, and baldly views patients as consumers of a service, it nonetheless stands to improve the doctor-patient relationship by clearly identifying motivations and needs.

A candidate milkshake mistake in medicine is the negative views about one of my favorite medical apps, Skin of Mine, which I've written about here. Physicians to whom I've shown the app often reject it, saying "patients want their doctor, not a phone," or "how can they trust it?" The potential milkshake mistake in these rejections is that many patients prioritize not missing work to get their skin evaluated above a face-to-face interaction with a doctor.

The crucial point for those, like Krugman, who rail against commodifying the doctor-patient relationship is this: until the market research is completed, we're just guessing whether "patients want their doctor," or whether they simply prefer convenience. Until we consider that patients are like consumers, we may in fact be cheapening the doctor-patient relationship by relegating how we optimize care to our own guesswork.

Tuesday, December 20, 2011

Threat Vs. Opportunity: Framing Change (in medicine)

Framed as Threat:

Advantages- Groups commit significant resources to face threats; their response is rarely insufficient. Also, they are more inclined to take risks.

Disadvantages- Groups' responses are typically rigid and based on strategies that worked well in the past; change "calcifies outdated models of how the world works."

Framed as Opportunity:

Advantages- Groups utilize more diverse, divergent, and creative thinking. They develop and capitalize on new strategies for achieving their goals.

Disadvantages- Groups don't commit sufficient resources and don't take risks.

Roberto concludes that the best response to change is, unsurprisingly, a mix of both. Groups should marshall significant resources, be prepared to take risks, but also encourage divergent and creative thinking while guarding against reliance on outdated strategies.

He uses the newspaper industry as an example. The most successful papers fully invested in exploring how they could use the internet to better tell the news by developing rich, interactive websites, incorporating bloggers, and publishing multimedia.

Perhaps this is a good lesson for how the medical world can consciously look to optimally frame the changes that the digital revolution hold for us? Here, I apply Roberto's five rules about optimal framing to the medical world:

Rule 1– Don't allow leaders to force their particular frame on those underneath them. Basically, allow doctors, residents, and med students the freedom to pursue their own vision, sheltered from insistance on what won't work.

Rule 2– Don't stick to one or two stock assumptions of the situation. Rather, welcome different overall perspective, some broad, some narrow. Perhaps embracing social media and other digital tools may relieve doctors' already considerable time burden?

Rule 3– Abandon hardened metaphors. Perhaps the doctor-patient relationship needs drastic revision?

Rule 4– Bring implicit assumptions to the surface. A classic is the assumption that patients want to see a doctor rather than wanting to feel their questions answered and to have solutions offered (see the rampant use of alternative therapies.)

Rule 5– Change the reference points. The need for truly patient-centered care is growing in relevance. Perhaps we should focus on patient concerns for empathy and communication rather than just disease status, like blood pressure and hemoglobin A1C.

Any contributions of examples for the five rules?

"The test of a first-rate intelligence is being able to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function." F. Scott Fitzgerald The Crack Up 1936

Monday, December 12, 2011

On the Edge: Social Media and Med Students

Le berceau (The Cradle) - Berthe Morisot 1872

There's a rich literature about the contributions that fringe, or edge, group members contribute to a field.

In his book Cognitive Surplus, Clay Shirky offers the example of Berthe Morisot's influence on impressionist painting. As a female, should could not have full membership in the impressionist club of the day, the Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers.

Rather than mitigating her impact, Morisot's edge status actually prompted more exposure of impressionism in the wider art community.

Shirky's point is that members operating at the margins of groups, members who are not full ensconced within a group's traditions and hierarchies, can be a broadening and enriching force.

And so, I submit to you that medical students are similarly on the edge, and can therefore broaden and enrich the applications of social media and other digital tech developments.

There's a rich literature about the contributions that fringe, or edge, group members contribute to a field.

In his book Cognitive Surplus, Clay Shirky offers the example of Berthe Morisot's influence on impressionist painting. As a female, should could not have full membership in the impressionist club of the day, the Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers.

Rather than mitigating her impact, Morisot's edge status actually prompted more exposure of impressionism in the wider art community.

Shirky's point is that members operating at the margins of groups, members who are not full ensconced within a group's traditions and hierarchies, can be a broadening and enriching force.

And so, I submit to you that medical students are similarly on the edge, and can therefore broaden and enrich the applications of social media and other digital tech developments.

Monday, November 14, 2011

Three Stages of a Profession

I propose the following stages of the medical profession:

Stage 1- From the time of Hippocrates and the birth of medicine, the best doctors knew how little they knew. Their main task was to humbly comfort.

Stage 2- Starting with antibiotics, knowledge started to equal treatment, and the best doctors sought as much knowledge as possible. Knowledge was power.

Stage 3- With the success of stage two, demographic shifts, and the advent of digital medicine, chronic disease abounds and the relevant knowledge is everywhere.

In this third and brand-new stage, I humbly propose that patients are best served not through seeking more knowledge, but in seeking creative and innovative applications of knowledge.

Medical education is run by the champions of stage 2, and they understandably encourage their charges to learn as much as possible.

Knowledge is certainly important, but patients need a medical education that serves stage 3. I wonder how to do that.

Stage 1- From the time of Hippocrates and the birth of medicine, the best doctors knew how little they knew. Their main task was to humbly comfort.

Stage 2- Starting with antibiotics, knowledge started to equal treatment, and the best doctors sought as much knowledge as possible. Knowledge was power.

Stage 3- With the success of stage two, demographic shifts, and the advent of digital medicine, chronic disease abounds and the relevant knowledge is everywhere.

In this third and brand-new stage, I humbly propose that patients are best served not through seeking more knowledge, but in seeking creative and innovative applications of knowledge.

Medical education is run by the champions of stage 2, and they understandably encourage their charges to learn as much as possible.

Knowledge is certainly important, but patients need a medical education that serves stage 3. I wonder how to do that.

Sunday, October 16, 2011

Singularity on a Plane

I had a delightful conversation on a plane (new for me) with a gentleman who was reading about Gettysburg. I was advocating futurism, he was celebrating history, but somehow, we both agreed with Ray Kurzweil. Things change at an ever increasing rate- what will happen when this rate is really, really fast?

Kurzweil's ideas are controversial, and I rarely share my enthusiasm for fear that I'll be labelled a freak. It took a conversation about the Civil War to build my confidence to defend Kurzweil here.

Kurzweil's main point is so simple, and yet so devastatingly undeniable, that even this older Gettysburg enthusiast supported it:

1. Things change. (Undeniable)

2. The pace of change itself is quickening (The Law of Accelerating Returns).

3. Will this continue to quicken? (History shows no significant slow-downs.)

4. What will happen when things change so fast that it's hard to keep up? (Kurzweil's guesses are fun.)

5. When will the pace of change reach this rate? (Read The Singularity is Near for more fun guesses.)

To dismiss these points as unimportant is cavalier. To dismiss those, like Kurzweil, who actively engage these questions and pose answers based on a solid look at evidence is not fair.

Why do I still feel nervous endorsing Kurzweil in public?

Kurzweil's ideas are controversial, and I rarely share my enthusiasm for fear that I'll be labelled a freak. It took a conversation about the Civil War to build my confidence to defend Kurzweil here.

Kurzweil's main point is so simple, and yet so devastatingly undeniable, that even this older Gettysburg enthusiast supported it:

1. Things change. (Undeniable)

2. The pace of change itself is quickening (The Law of Accelerating Returns).

3. Will this continue to quicken? (History shows no significant slow-downs.)

4. What will happen when things change so fast that it's hard to keep up? (Kurzweil's guesses are fun.)

5. When will the pace of change reach this rate? (Read The Singularity is Near for more fun guesses.)

To dismiss these points as unimportant is cavalier. To dismiss those, like Kurzweil, who actively engage these questions and pose answers based on a solid look at evidence is not fair.

Why do I still feel nervous endorsing Kurzweil in public?

The Head Down: Alone together

I've started conversing with strangers in elevators.

After reading Sherry Turkle's Alone Together: Why we expect more from our technology and less from each other, I've become uncomfortable when I find myself with three or four others, head down, peering at my phone in an elevator. Or walking past someone in the hall, head down, both of us making our way slowly by sheer dint of peripheral vision.

Before reading Turkle (and really, up until the epilogue of her book), I was dismissive of any critique of the head down. Our phones connect us in rich, genuine ways, with those we care about. They also forge new relationships with those we might not meet otherwise. Best of all, phones enable us to transcend the fickle bondage of location and even time to interact with those who otherwise just aren't here. Most of Turkle's book fell flat as she, like so many other critics, brushed these attributes aside, and instead embraced the tired bromides about why I don't "just call" my "real" friends.

Now, I've admitted to myself that I just feel uncomfortable when head down. When I see the head down, I react similarly to when I see teenagers all conforming to the same fashion trend, clearly more interested in fitting in than being themselves.

And this, according to thinkers from Ken Wilber to Clay Shirky and, most recently, Michael Chorost*, is the real issue. Connectedness is fitting in, at the opposite end of a spectrum from disconnection, which is standing out. Our lives are somewhere in between, and our personalities place us closer to one pole or the other. Neither pole is right or wrong, and where you are depends on your comfort.

I like to stand out, but that's just me. I try not to give other people a hard time for when and where and how often they prefer to fit in (so long as they stop meandering down the hallway), and I certainly won't castigate our new way of life as somehow a degradation of a better time.

Maybe the other stand out people are just upset because they're losing what used to be a captive audience?

*Chorost's new book World Wide Mind is really a great piece of writing, as well as eye-opening.

Friday, October 7, 2011

How A Disruptive App Disrupts: Skin of Mine

Skin of Mine is an impressive tool that allows the analysis of one's skin condition (from acne to psoriasis, moles, vitiligo, and more) with nothing more than an iPhone.

To appreciate the nature of a disruptive innovation, see how this app changes the very structure of the doctor-patient relationship.

Traditional:

1. Call primary care doctor and schedule appointment.

2. Take time off from work etc. to see primary doc.

3. Get referral to dermatologist.

4. Call dermatologist to schedule visit.

5. Take time off from work etc. to see dermatologist.

6. Act on diagnosis and prescription.

7. Call to schedule appropriate follow up.

Disruptive:

1. Take picture, complete a questionnaire, and submit to the expert of your choice.

2. Receive diagnosis, prescription, and therapeutic advice within 24 hours.

3. Act on diagnosis and prescription.

4. Call or use app to schedule appropriate follow up.

Crucial Points:

The app obviates two office visits and the time needed off from work.

The app is faster.

One health care provider and many staff are cut out of the loop.

The patient has a personal record of what happened.

Note: I have no connection with or support from Skin of Mine

Thursday, October 6, 2011

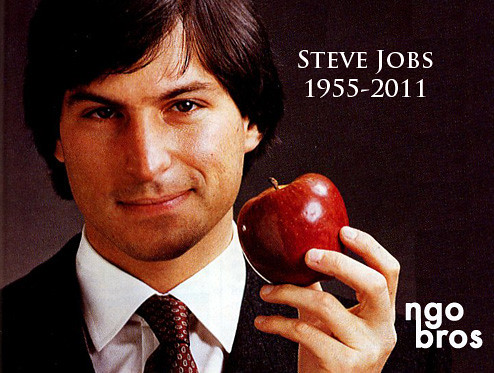

Losing Jobs Matters

The passing of Steve Jobs matters; technology will be less human than it could be.

Apple is one of the world's most influential organizations, not by sheer wealth, but by impact across variegated industries beyond technology: music, publishing, retail, and more.

Yet, as beautifully detailed by David Pogue Steve Jobs: Imitated, Never Duplicated, this influence was created and wielded by an iconoclast. Lots of companies are run by geniuses, but Jobs defined himself by running against the grain, doing things "wrong," and yet hewing to principle's of beauty that engendered cult status.

I can't imagine a board electing a CEO who, like Jobs, dropped out of college, never worked for anyone else, and simply didn't give a damn what other people thought.

So how did Jobs wind up running one of the world's top companies? It's because he built it, and he did so at the time of the industry's inception. Since the computer industry is long past its inception, we can be confident that it simply won't see another titanic iconoclast at the helm.

And this is a great loss.

Innovations will continue to pour out at an accelerating pace, but they will not cut to the soul as beautifully as those created in the world of Jobs. Simply put, Apple makes products that are, above all, powerfully human.

Is there another force on this planet as powerfully human-oriented than Apple? Oriented in practice, not simply ideology or disposition? I submit that the key was Jobs's deep, micro-managing, hands-on involvement in production, bringing the corporate might Apple to bear on the most minute impediments for common users to achieve their goals.

The entire might of one of the wealthiest companies was, for a time, directed at removing the impediments of common people from achieving their desires.

According to Pogue, there will not be another Steve Jobs, ever, and we are worse off for it.

Wednesday, October 5, 2011

How To Look Serious With Your Phone (5 Tips)

It happens daily. I'm faced with some serious work that can easily be handled with my phone, but I'm nervous to pull it out of my pocket. In the medical world in particular, the workplace is not a time for mobile frivolity, and skeptics abound.

Here are my five tips for looking serious when being serious with your phone.

1. Hold a pen in one hand. It just looks like you're working instead of chatting, I suspect it reminds onlookers of the Palm Pilots of yesteryear. I like to extend the pinky finger of the hand that's holding the pen. I'll occasionally draw attention to my pen by subtly tapping it against my forehead or pressing it against my temple, just to create the sell that I'm being serious here. If you're more adventurous, use another prop like a book- just holding it open can look like you're cross-referencing. Very serious.

2. Cradle with care. Hold the phone in your non-dominate hand, and tap at it with your dominate hand. If available, set the phone on a table. This looks like you're engaged in a task and either entering or manipulating content, rather than just consuming it. Even when I'm typing into a text field, I hunt-and-peck with one finger so that it doesn't look like I'm texting.

3. Don't hunch. Don't be caught cradling the phone in both hands, elbows bent, hunched over the screen like you're texting or trying to view someone's profile picture. If the phone is at a distance, it looks like you are open to sharing its content with others around you, creating the semblance that you are accessing professional material.

4. Share your screen. As often as possible, engage others around you in the content you are consuming. This helps establish you as a serious user because others can see that you're not fooling around. Additionally, it promotes the idea that a phone can have serious uses. Furthermore, even if you aren't shutting people out while engrossed in your phone, it's polite not to LOOK like you're shutting others out. However, be careful not to be that guy who is gleefully showing everyone how irrelevant they all are thanks to your snappy apps. (Even if you think it's true.)

5. Adopt a pensive look. This seems trivial, but really, who texts or scans Facebook with a knit brow and protruding lips? If the app is making you think, look like you are thinking (even if you're not).

Any other tips out there?

Tuesday, October 4, 2011

Disruption in the Doctor's Office

Traditionally, new technologies reached medicine in a top-down direction. The invention of MRI, for example, was first introduced to hospital administrators and department chairs as a potential new diagnostic tool. Once accepted, others further down in the medical hierarchy gained exposure.

This technology wasn't disruptive because it didn't change the overall structure of the field. As before, patients still came to hospitals for sophisticated diagnostic work-ups, only now the hospital had a better, albeit more expensive, tool.

Many of today's medical technologies are disruptive, which is different.

Take, for example, the iPhone app Skin of Mine. Take a picture of a suspicious mole and get either automated analysis about its likelihood of melanoma, or an online consultation with a dermatologist.

This invention is entirely unlike the MRI scenario. Instead of entering the field from the top down, it comes from the bottom up. Patients can walk into their doctor's office with this invention already in their pocket, asking questions about a diagnosis made by their free mobile app, all without the department chair or hospital administration even knowing of its existence.

This changes the overall structure of the field: the patient has direct and cheap access to diagnostics, less need for an office visit, and more information in the patient's hands.

A crucial question for medice is how to respond to disruptive changes that come from the bottom up? My guess is that most clinicians, understandably, will not take kindly to innovations that reorganize their workflow. The nightmare of adopting a new EMR is trivial compared to the challenge of restructuring how and where a doctor sees patients. Nonetheless, I'm guessing this change will be inevitable as patients clamber for the cheap convenience of such disruptive technologies.

Personally, I think medical schools hold the key to ushering this bottom-up transformation. They can serve as the field-testing ground for disruptive innovations, training the near-future doctors as well as offering exposure to their more entrenched clinicians, but in a structured way that blunts the stress of disruption.

Saturday, September 24, 2011

Three trends on the future of the medical profession, with links.

Ruminations on a profession:

Kent Bottles (@kentbottles) has a great piece:The Effect of the Information Revolution on American Medical Schools. It's a bit dated, but his opening comments on the nature of the medical professoin are golden.

Trend 1: Explosion of information tech and its consequences for medicine.

A GREAT 18 minute TEDtalk by Daniel Kraft: Medicine's Future? There's an app for that. (It's about leveraging cross-disciplinary, exponentially growing, technologies.)

Another fascinating TEDTalk by Eric Topol: The Wireless Future of Medicine. Many of these topics are covered in the Kraft talk, but it offers a wider survey of the gadgets.

Trend 2: Disruptive innovate is coming.

The bible on this topic is The Innovator's Prescription by Clayton Christensen and others. Disruptive Innovation in Health Care Delivery provides a synopsis of the major concepts. (This one might be a little painful- hang in there through the business model talk- t's worth it.)

Trend 3: Social Media is coming.

Clay Shirky is the guru of social media (a philosopher and a sociologist). He has two TEDTalks, the first is about group formation and action. It's from 2005 and not specifically about healthcare, but it doesn't take a lot of imagination to apply it to healthcare. The second is more about information streams, and the same goes. Specifically, he details the power of groups to usurp professionals.

If you have the time, Shirky's newest book Here Comes Everybody is a great, great read.

Of course, feel free to explore your own topics and content- these are just some suggested guidelines.

I'm excited for this session! Of course, let me know if you have questions.

Until then,

-Aaron

Sunday, September 4, 2011

Protecting institutions from medical students

It may be helpful to sort policy goals for students into three categories:

1- How to protect patients.

2- How to protect institutions.

3- How to protect students themselves.

This post addresses protecting institutions. I offer some typical institution-relevant guidelines, and then give my two cents. Your thoughts are greatly appreciated.

Good guidelines for protecting institutions that I've come across:

Be factually correct- don't overstate your knowledge.

Be transparent- disclose your connection to and your role with the institution your institution.

Control your institution email address- only use you .edu address for official business.

Control your privacy settings.

Weak guidelines:

Adhere to the institution pledge/code- pledges and codes offer few specifics.

Obtain permission- what warrants permission? Every single tweet? Blog posts that mention the institution?

My Two Cents:

One of the

first things newly minted medical students do is sew their school’s

seal on their white coat, offering a continual reminder that they represent

their medical institution whenever they wear this coat. However, they do not

have any badge to remind them of this when they are online.

Medical school has

particular demands and stresses beyond those of many other educational

settings. In my experience, stress and unhappiness were commonly transferred to

professors, courses, and the institution as a whole, often with discomfiting

vehemence. It was not uncommon to see these expressions find their way to

facebook.

More than

simply protecting themselves, medical schools owe it to their students to

prepare them to represent the institutions to which they will belong in the

future. As future doctors, medical students will find themselves building and

maintaining professional relationships for decades, each with different

cultures and expectations of openness, sharing, and representation. The earlier

these skills are developed, the better off students will be.

Many of the

obligations and features of operating in the social media space derive from issues

of professionalism. Social media training is an opportunity to teach

professionalism, not only in content but also in practice. In my experience,

features of professionalism have been taught didactically, and participation

has consisted only of personal reflection. Social media training, specifically

regarding representing an institution, offers a means to actively engage

students with these crucial issues.

How do we

protect institutions from students’ damaging comments, made deliberately or

spur-of-the-moment? Again, the middle way between abstinence and indifference

lies in student training about creating content that appropriately represents

those to whom institutional membership impinges upon. A first step is to

characterize for students the nature and extent of their obligations to the

institution. The specific stakeholders who depend on the institution’s “good

name” should be detailed, along with their depth of connection. A potential

method is to start with the individual student and work outward. When you speak

about your school, you are indirectly speaking for yourself, your classmates,

all students, and all alumni who have dedicated years of study and will have/do

have certification/validation of their life’s calling in the form of diplomas.

You speak for the faculty and staff who have staked their livelihood on service

to the institution. You speak for the administration who have staked their

professional reputations. You speak for the clinicians you aspire to be. You

speak for the patients who have chosen to be treated here. You speak for the

community members who respect your institution as an integral community

fixture.

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

What Can You Say in an Elevator? Protecting patients from medical students

I have argued previously that, prior to encouraging medical students to engage with social media, we should establish guidelines to protect patients, institutions, and students themselves from naive transgressions.

My post received some welcomed criticism for being overly conservative. Here, I outline my specific concerns about the subtleties of the risks medical students pose to patients.

As the number one priority of medicine, patients should be the number one privacy concern for medical schools. Patients are the most vulnerable stakeholders in the social media health space. Not only is their information the most potent, but their engagement with the medical profession explicitly entails protection of this information by a professional organization that is trained and federally mandated to do so. While the laws and consequences are detailed in the HIPPA documentation, medical students are rarely offered more insight than the commandment “Do not share patient information.”

Here's why I think we need much more than such simplistic admonitions.

Medical students are expected to share patient information all the time, and it is considered appropriate to discuss patients so long as they can’t be identified, but how can one be sure? Is it appropriate to discuss the particulars of a patient in a full elevator, so long as their name and demographics are left out? Can anything about the patient at all be discussed in an elevator? If the patient has heart disease, surely it’s okay to discuss the pathophysiology of the disease itself. But what if they have a rare condition? Isn’t it possible that discussion of a rare cardiac abnormality while stepping into an elevator may occur in the presence of family members leaving that elevator? Isn’t it likely that they may have just been Googling their loved-one’s symptoms and have that rare abnormality on their minds? The point is to illustrate the subtleties that are glossed over by the admonition “don’t share patient information.” If such subtleties exist on elevators, surely there is even more grey territory in social media situations. For example, it is not uncommon for students to post status updates about interesting cases. If something like “I saw Ebstein’s abnormality today!” were posted as a status update, it is conceivable that a distant friend viewing that update may connect this with a family member. Worse still are the consequences of a student blogging about such an experience.

While we trust physicians to exercise appropriate judgment in these areas, we cannot expect medical students to have the knowledge and experience to make these judgments. Before the advent of social media, students simply did not have to worry about broadcasting patient information because the traditional media, print and television reporters, did not approach medical students for stories. If a medical student did find themselves in such a position, they were likely sophisticated enough to earn such interest and therefore mature enough to control their comments. In the connected age, however, medical students’ comments may instead find wide distribution specifically because they have injudiciously, and unknowingly, said things they shouldn’t.

How do we adequately protect patients from such inadvertent transgressions? One option is to demand student abstinence from including medical content of any kind in the social media space. While tempting, this position is both unenforceable (social media and medicine are central to students’ lives) and excessively restrictive (prohibiting medical content on social media deprives students the opportunity to learn the many beneficial potentials of social media use in the healthcare space). The alternative, unfettered use, is equally untenable. The best path toward patient protection would be student training in appropriate use.

What would this training look like?

Are there examples out there?

Friday, August 12, 2011

Social media risks for medical students

Social media use by medical students is a dangerous proposition for five reasons:

1) The information that medical students steward is particularly sensitive, has massive consequences for the vulnerable populations from which it's drawn, and the privacy of which is protected by federal law.

2) Sharing this information with one’s colleagues and superiors, in write-ups, presentations, and casual discussion, is expected as part of a med student's medical education. Doing so appropriately within the traditional contexts is hard enough without trying to determine what's tweetable.

3) Medical students have a lot to lose, both in terms of resources invested and future career ramifications, if they are found in violation of patient privacy, if they insult their school, or if they say something boneheaded. Crucially, students are often naive to their own personal stakes.

4) As digital natives (having matured entirely in the connected, internet age), today’s medical students have deeply ingrained information sharing habits that may be incommensurate with their new responsibilities.

5) There is a growing body of MD’s, healthcare workers, and commentators who encourage medical students to engage with social media as a central feature of medical education and future practice without adequately preparing these students to be responsible (and often without consensus even amongst themselves).

Three concerns come to mind:

1) How do we protect patients?

2) How do we protect institutions?

3) How do we protect students themselves?

Until we can robustly offer these three protections, I do not think it is right to encourage medical students to join the social media space.

Am I being overly cautionary?

Am I missing any areas of protection?

Your thoughts are SO, so welcome!

The Listening Tour: Teaching, learning, and social media at academic hospitals

Hillary Clinton came through my little Upstate NY town in 1999 to kick off a “listening tour” on her senate campaign in which she handily defeated challenger Rick Lazio. She demonstrated the power of starting by listening.

Academic hospitals can channel the same power to broaden their reach, and teach.

The first step in launching a social media strategy, according to Hive Strategies, is to listen:

Listen to how patients are talking in the waiting rooms. Listen to the questions new moms in your birthing center are asking nurses. Go to the FAQ web pages created by your Centers to read what they feel are the issues of key concern to patients. Go sit next to the person who answers the hospital’s main phone line. What questions is he or she answering for patients? Listen to the voicemail introductions of each of your centers to give you insight into what the managers think their patients need to know? Listen to the conversations in Emergency Rooms. Listen to what your patients are saying on patient surveys, and listen to how the media talks about your hospital.

What if medical students were used to do this listening as an elective? They would gain exposure to the real needs of various stakeholders in healthcare. Reporting on their discoveries, they could research supporting evidence and share it using a social media tool like Yammer. All the students working on such a project could upload their findings and discuss them in a common, secure web document that could serve as an informative portfolio for the social media strategy.

Such a listening tour would offer students valuable insight into the realities of healthcare barriers and quality issues, as well as some exposure to the applications of social media both to share information and tackle these barriers to deliver better care. The hospital would get free “boots on the ground” for the fact-finding step as they reach to claim the mantle of "healthcare innovator." The college of medicine gets their students talking about issues and passing them along to the whole class, as well as incorporating social media into the curriculum. And, some day, patients get better care.

Wednesday, July 27, 2011

How to get started with Twitter (QUICKLY)

I've outlined 10 quick steps to getting started, in video and text. Play the video while looking at the text?

1. Sign in at twitter.com.

*Your username will become your identifying "handle." I recommend going professional. I'm @astupple.

2. Click the drop-down at the upper right, choose "settings," and attend to "tweet privacy."

*Before you share content, decide if you want it public.

3. Click "profile" and upload a picture.

*Better to use a photo of your cat than nothing- otherwise people will think you're a spammer.

4. From the homepage, click "who to follow" and enter "@astupple," "@westr," and "@kentbottles."

*You can sample our "feeds" by clicking on the links.

5. "Twitter clients" are programs, apps, and extensions that interface with twitter better than the website.

*I recommend the web browser extension "chromed bird" for google chrome. Fast. So fast and easy.

*Others love "tweetdeck" and "hootsuite" as desktop programs to use instead of the twitter website.

*For your phone, I like the "echofon" app, but tweetdeck and hootsuite apps are great too.

6. Know this: Only those who follow you will see your tweets EXCEPT...

*If you include a handle, @JohnDoe, in the tweet, then John Doe will see it even if he doesn't follow you.

*If you include a hashtag, #thebeatles, then anyone following or searching #thebeatles can see it.

*If someone searches your for terms that you used in your tweet, they MIGHT see it.

7. Q few quick terms:

*Tweet- Any time you send a message via twitter.

*Retweet- You resend a message that someone else tweeted, the originator notices (and appreciates it)

*Reply- A tweet that starts with someone's handle, it's viewable by your followers who follow that person.

*Direct Message (DM's)- Private message someone by entering "d astupple Blah blah blah..."

8. When including links, shorten them with services like tinyurl.com or bitly.com.

*The twitter clients usually do this automatically, you'll get a sense of how to condense links quickly.

9. If you want to see crazy, sign in to tweetchat.com Sundays at 9PM and enter "HCSM."

*I dare you. (It's the H.ealth C.are S.ocial M.edia weekly tweetchat and it's FUN.)

10. Finally, I'd follow @tweetsmarter to get LOTS of great tips on Twitter use and everything else.

*The Twitter Guidebook answers questions like "What is a hashtag?" and others far better than me.

Happy tweeting!

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

Twitter is a vastly rich medium that's worth your time.

It's 10 minutes, and it's all been said before, but I hope this video is worth your time.

Summarized below are three reasons (among many more) to give Twitter a shot.

1. Taking

You don't have to give in order to receive. By following people without ever delivering a keystroke, you can quickly consume information that is relevant to your interests. Like surgery? Follow Atul Gawnde (@Atul_Gawande). Curious about the latest in neurology? Check out @NeurologyNow. Interested in healthcare policy? Follow @GarySchwitzer. Thirst for everything? @KevinMD and @KentBottles.

2. Giving

If you want to create content, there are gradations of involvement. You can innocuously resend what you thought was interesting (called retweeting), or post websites that interest you, along with short descriptors. More boldly, you can share experiences, make statements and judgements, or use Twitter to broadcast your own creations (warning- you might find yourself creating a blog and posting videos about how awesome you think it all is). See how medical student Allison Greco unifies blog and Twitter at md2bGrecoa3.com and on Twitter as @GrecoA3, or gastroenterologist Bryan Vartabedian at 33charts.com, @Doctor_V.

3. Networking

While conventional circumstances narrow who we get to know in this world, Twitter offers a great way to connect with people we don't know but who otherwise share our interests, our quirky insights, idiosyncratic hangups, or outrageous perspective. If nothing else, consider establishing a Twitter account before attending your next conference, whereby you'll more easily meet attendees with your motivation. And, it's not just for connecting with those across the country, but also for meeting local people and maintaining relationships you've already started. I know @Peds_ID_doc pretty well, and gain much clinical insight, considering I'm rarely physically in his presence on the floors.

Caution: Don't say anything that would would bother you were it printed in the newspaper. Envision each tweet on a billboard outside your hospital. In the digital world, it's hard to know where the walls are that enclose your statements, and depending on your personality, it's easy to lose yourself, or to outright forget yourself, and say something boneheaded (or worse).

Monday, July 25, 2011

Aphorisms and The Black Swan and Twitter

The most compelling aspect of Nicholas Nassim Taleb's book The Black Swan was his dissection of the narrative fallacy. We continually concoct explanatory stories to comfort ourselves in the face of an irreducibly complex world. Crucially, stories compel not only by their truth, but by their very nature as stories. (Taleb cites those fantastic split-brain experiments where intelligent patients, faced with their own obviously contradictory behavior, will fabricate wild explanations without hesitation or doubt.)

However, stories often fail (even the best inevitably fail at the hands of unpredictable, rare, black swan events), and we rewrite our stories and hang on until they fail again.

But these stories do have kernels of insight and nuggets of experiential wisdom. How do we pluck out the insight?

Enter the aphorism, short statements that focus on the insight and dispense with the time-consuming and misleading narrative. Nietzsche authored many of my favorites:

"A casual stroll through the lunatic asylum shows that faith does not prove anything."

"Admiration for a quality or an art can be so strong that it deters us from striving to possess it."

Are Twitter, status updates, and the sound bites of social media digital aphorisms, dispensing with the narrative and going straight for the insight?

Saturday, July 16, 2011

The Race Is On: To the victor go the spoils (of 21st century medicine)

In the past, the medical profession was aware of groundbreaking technologies and applications well in advance of patients. Their first experience with EKG’s and genetic testing was mediated by their doctor from the beginning. Today however, patients can get their hands on mountains of genetic data through the mail at the price of a fancy meal. As these tools are made ever cheaper and more sophisticated, as inexpensive and inobtrusive devices are networked with smartphones and mobile health apps, and as patients increasingly adopt these tools in an effort to define themselves as empowered members of the doctor-patient relationship, the traditional medical world will be trying to catch-up. Today’s doctors will have to learn how to adopt these advances into their practice on their own, and it’s hard to think of a better time to start than now. The challenge of a patient armed with a dossier of Google searches pales in comparison to an empowered patient who has the motivation and time to enlist several features of 21st century medicine: direct-to-consumer genomics, mobile health apps, personalized medicine, social media tools, personalized health records, and more.

While the current medical education curriculum still labors under an educationally conservative structure, medical students might paradoxically see great opportunity. Today’s medical students are largely digital natives who, importantly, have not been shaped by what has been described as a bygone era of medicine. They are uniquely suited to learning about these breakthroughs, experimenting with the devices and tools, and innovating their application. In the teaching hospital, the medical student can familiarize his or her superiors with the tools while gaining insight into effective uses. Thereafter, medical graduates so informed would be highly sought after to shape the clinical and commercial future of these initiatives. There is a wealth of opportunities for the student who buys a BodyMedia armband and talks about it with clinical faculty while on the wards, or, by comparing their experiences interviewing patients in the clinic with the dialog at PatientsLikeMe.com, becomes proficient at distinguishing what patients want to know from what is helpful to know. Precisely because medical schools struggle to incorporate this material into a curriculum means that students who take the initiative to become proficient in 21st century medicine stand to be particularly valuable to many stakeholders in the healthcare field.

Wednesday, July 13, 2011

Why the FitBit is FanTastic.

Photo: www.FitBit.com

Being healthier means a lot of different things, but one commonality to almost any health improvement is that, at some point, it will be hurt a little to run a mile, forego an ice cream, or down some cabbage. And that's why the FitBit is the best health tracking tool there is:

It's painless.

You put this tiny clip on your person and then forget it's there. It can go a week between charges, all the while recording your steps and calculating your total calories burned. And when you're within 15 feet of your computer, it uploads your data wirelessly (provided the hub is attached by USB). And. That's. It.

Even the fee schedule for the fitbit is painless. The device costs $100, and the basic web analytics are free--if you want, you can upgrade to more web features for a fee. Again, painless.* I've been using it for 7 months and haven't had a day go unmeasured.

This is a point too easily lost: people don't necessarily want more features, they want less pain. (David Pogue engagingly demonstrates this truth here.) The makers of health apps and health games and tracking tools and health devices need to understand that most people want less tasks to do, and less to think about, rather than more. (See my post about apportioning our cognitive resources.)

Bells and whistles often become work, and living healthy is already a full time job.

*Compare FitBit to the BodyMedia armband. It's accuracy is unparalleled, and it's able to measure your calories burned even while watching TV and sleeping. The web profile is flashy, and there's a great smartphone app that enables you to watch your data in real time. And... it's a little painful.

Note: I have no affiliation with FitBit and no axe to grind with BodyMedia.

Being healthier means a lot of different things, but one commonality to almost any health improvement is that, at some point, it will be hurt a little to run a mile, forego an ice cream, or down some cabbage. And that's why the FitBit is the best health tracking tool there is:

It's painless.

You put this tiny clip on your person and then forget it's there. It can go a week between charges, all the while recording your steps and calculating your total calories burned. And when you're within 15 feet of your computer, it uploads your data wirelessly (provided the hub is attached by USB). And. That's. It.

Even the fee schedule for the fitbit is painless. The device costs $100, and the basic web analytics are free--if you want, you can upgrade to more web features for a fee. Again, painless.* I've been using it for 7 months and haven't had a day go unmeasured.

This is a point too easily lost: people don't necessarily want more features, they want less pain. (David Pogue engagingly demonstrates this truth here.) The makers of health apps and health games and tracking tools and health devices need to understand that most people want less tasks to do, and less to think about, rather than more. (See my post about apportioning our cognitive resources.)

Bells and whistles often become work, and living healthy is already a full time job.

*Compare FitBit to the BodyMedia armband. It's accuracy is unparalleled, and it's able to measure your calories burned even while watching TV and sleeping. The web profile is flashy, and there's a great smartphone app that enables you to watch your data in real time. And... it's a little painful.

The armband is bulky (how do you wear it at work?), you have to take it off and physically plug it into your computer every day, and there's an unavoidable monthly fee. It's painful.

Note: I have no affiliation with FitBit and no axe to grind with BodyMedia.

Dirk Nowitzki gave me mad props today, and it was awesome.

My Nike+GPS app had a message for me at the end of my run today, and it was from Dirk Nowitzki: "Hey, this is Dirk Nowitzki, and I just wanted to give you mad props for making it out there today."

I couldn't be much more of a cynic, and I HATE patronizing flattery, and what could be more baldly obvious than that a corporate behemoth was shamelessly using a celebrity to make me feel good about buying and using its products? By all rights, I should be sick.

But if I don't get bummed some canned words of encouragement at the end of a run, I'm a little bummed.

The tiny fraction I know about Dirk NowitzkiI is that he's well regarded as a dedicated player and a stand-up guy. When I imagine Mr. Nowitzki sitting in a sound booth somewhere recording his stock accolades, I'm pretty sure he is, in no small degree, genuinely happy for me. I bet he's happy to be encouraging legions of minor athletes out there, and genuinely wants us to keep at it. And it works.

Imagine if it was stock commentary from my doctor?

Sunday, July 10, 2011

Getting Played: 3 design thoughts for improving buy-in for mobile health apps.

Just because it's a game doesn't mean it's fun.* With angry birds, you simply fire up the app and start poking at the screen, but in health games you have to do something you'd rather not- eat a vegetable or run a mile or climb some stairs. To overcome this....

It would be simple.

In any game, there's a gap between input of time, energy, and focus, and the output of points earned, leveling up, or saving the princess. While some games thrive on a wide gap that's filled with a rich story line, engaging graphics, or intricate maneuvers, my health app would have a strict minimum of futzing around. This is because, by the time I reach for the health app icon, I've already crossed much of my gap, and I'm ready for my reward. Now.

It would be social.

Yes, social is all the rage, and rightly so. A less obvious feature of the value of social is that it enables healthy people to encourage close friends and family to be healthy, without precipitating an intervention. Motivating loved ones to eat better and exercise is tricky if you don't want to bring anxiety, guilt, and tension into a relationship. A social game is a perfect way for healthy people to casually encourage others, as well to stay motivated themselves.

It would include your doctor.

A family doc I worked with had some success with his own personal diet brochure. It was especially successful because he had personally lost much weight with it. What if he could point patients to a social game app that he himself played too? Consider the ramifications: The doctor's advice about eating better and exercising doesn't end at the office door. The app is good branding for the physician's practice. Buy-in soars because the virtual presence of patients' doctor connects healthy lifestyle choices with significant disease. Hospitals can adopt it as well, and there are lots of hospitals with lots of money. Local businesses can support it too by advertising their healthy offerings of food, gyms, or exercise equipment. I dare say this is only scratching the surface....

*Check out Jane McGonigal's TEDTalk on solving problems, including obesity, with games.

Wednesday, July 6, 2011

On Surgery, etc.: Revenge of the Nerds

I laughed out loud. Several times. This is, objectively, really funny. About why docs are slow to social media.

Monday, July 4, 2011

A Phalanx of Mobile Apps: Just What the Doctor Ordered

"The Cavalry Charge" -Frederick Remington

"Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them. Operations of thought are like cavalry charges in a battle — they are strictly limited in number, they require fresh horses, and must only be made at decisive moments." - Alfred North Whitehead An Introduction to Mathematics

Using an app in place of a thoughtful operation is, to borrow Whitehead's phrase, like mounting a cavalry charge, but without having to refresh the neural horses.

Since our brains are finite, capable of only so many cavalry charges a day, progress is two-pronged. It both increases the number of cavalry charges, and continuously promotes the brain to the vanguard. The more apps come along, the more operations are completed, and the more the brain is liberated from mundane operations and promoted to the forefront of what really counts in our day. Crucially, I don't see apps as dumbing us down, but rather, as smartening us up to perform previously unreachable operations of thought.

Today, when I'm faced with the need to operate thought, a little voice asks if "there's an app for that"? It's really not a modern question, but a primitive reflex rustling about in the wisdom of Whitehead's statement. Humans have always sought tools to solve problems that buy us more time to solve more problems (that buy us more time to solve more problems, á la Ray Kurzweil). We corralled herds of mammoth off cliffs to save the time and effort of hunting them one-by-one. There's no real difference when we use the Chipotle app to save the time and effort of waiting in line.

Much has been made of the impact of apps on healthcare (See Kent Bottles's post for a trove of examples). But I believe the biggest impact has yet to be richly explored, and that is the the quantified self movement.

Briefly: consider that monitoring the effects of our behavior clearly benefits our health (See Thomas Goetz's The Decision Tree blog for examples). The trouble is, we behave all day long, and continuously monitoring our the effects of our behavior would use up a lot of cavalry charges. Given that chronic disease is the costliest aspect of healthcare, and that lifestyle choices such as diet, exercise, and smoking are key contributors to such chronic conditions as congestive heart failure, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, then a phalanx of mobile apps might be just what the doctor ordered.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

,_1872.jpg/487px-Berthe_Morisot,_Le_berceau_(The_Cradle),_1872.jpg)